For pretty much most of my adult life I have been regretting the fact that we do not teach languages effectively in Ireland. One of my key concerns is that as a country, Ireland does not value those skills.

During the week, Richard Bruton, Minister for Education, announced that in the future, all students for the Junior Certificate (this is the exam taken at around age 15 or 16 in Ireland) would study a foreign language. He is quoted as saying a couple of things which interested me:

“We are going to have to, post-Brexit, realise that one of the common weaknesses of English speaking countries – that we disregard foreign languages – has to be addressed in Ireland.

He is also targeting a 10% increase in the number of students taking languages at Leaving Certificate level. There is also a desire to expand the range of languages taught in Irish schools. All of this is laudable.

“We need now to trade in the growth areas – and many of those speak Spanish, Portuguese and Mandarin. Those are the languages that we need to learn to continue to trade successfully.”

One of the key issues which we need to address, however, is the lack of teachers in these areas. And we need to take a long hard look at how successful we have been with the more common languages like French. It is one thing to say we will teach more languages. It is an entirely different kettle of fish when it comes to acknowledging we have made a hamfisted mess of it so far. We teach people Irish from the age of 5 and have not yet got that right for example.

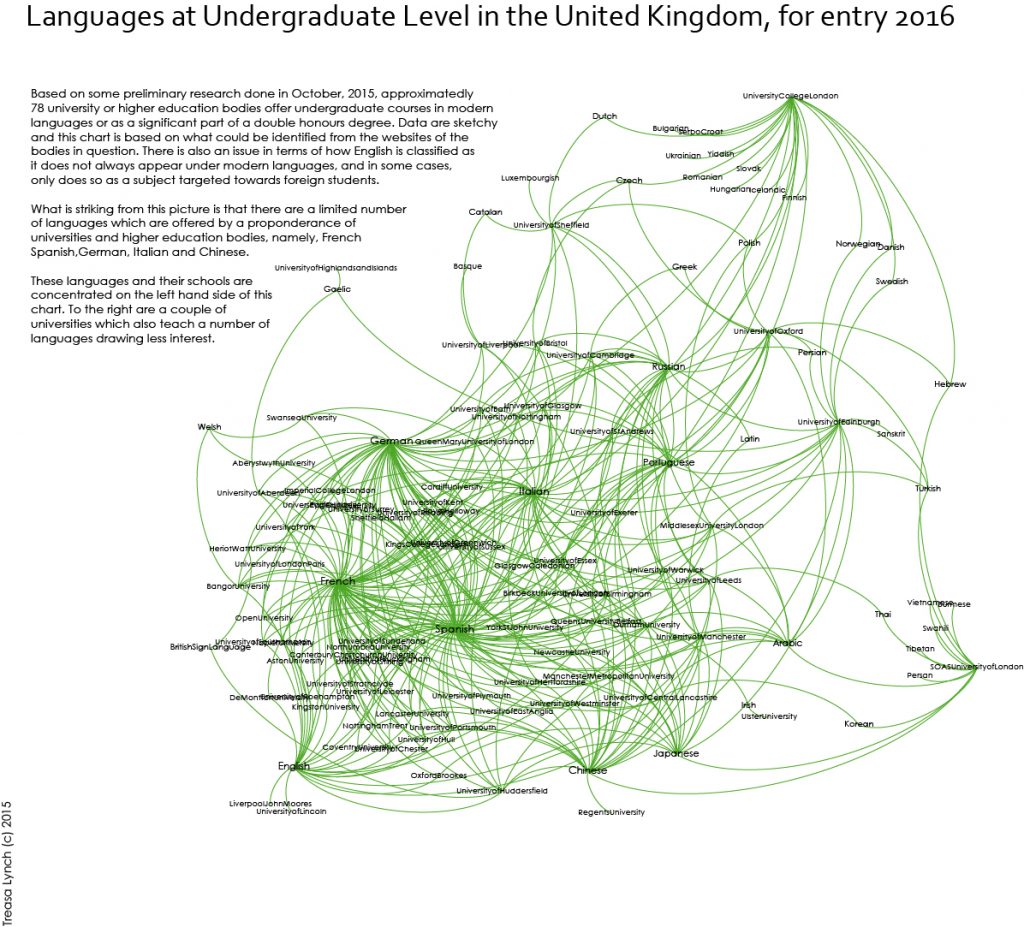

There are other issues. If you take a look at the availability of languages at third level, you’ll find Spanish has reasonable coverage. The others do not. It might be possible to take Portuguese in UCC under their world languages program but most common across the university system in Ireland are French, German and Spanish with possibly Japanese as the outlier.

Against that, in absolute terms, more students study foreign languages in Ireland (even if we don’t count Irish as a second language) than do in England and Wales.

On the plus side, I’m really happy to see that there is a will to fix the gaps in foreign language acquisition in the Irish school system. But I think there is a lot to do outside simply putting a curriculum together and getting kids to study it at school. What does not support language acquisition in Ireland is the chronic lack of credible media in foreign languages. If you listen to radio in most European countries, they are playing a wider range of pop music in a bunch of different languages. Our media is incredibly anglo centric. When I was at school in the 1980s there were two French pop songs in the charts, one called Voyage Voyage and one called Joe Le Taxi (it catapulted Vanessa Paradis into the big time). Foreign language television tends to be relegated to the smaller stations, in Ireland TG 4 and in the UK, BBC 4. The rep for TV5 has his heart broken on twitter trying to make it clear that TV5Europe is available on most sat systems available in Ireland.

I learned an awful lot of my French by watching of all things Beverly Hills 90210 dubbed into French.

If we are going to say “We, in Ireland, recognise that we need to learn foreign languages”, we also need to say “And we will try and get the media to get their asses in gear to support this”.

In a way, this is recognised by his counterpart in opposition, Thomas Byrne.

Any modern language strategy must be across all Government departments as well. It can’t just be about the education system – it has to be how we live our lives, how we interact with the wider world.

I’d also add that in one respect, I think that Richard Bruton maybe should reconsider this:

At the moment if you look at Leaving Cert and Junior Cert, French dominates. French is a lovely language, but we need to recognise that we need to diversify into other languages

In the grand scheme of things, he is probably aware that a stated element of Irish foreign policy at the moment is to encourage and support as many people as the country can into the European institutions. One of the key issues we have in this respect is that not enough people come out of school with fluent French or German. We may need to diversity into other languages but I think we need to ensure that in the future, we are not looking at one foreign language, but two and that Irish people have a command of two of the working languages of the institutions of the European Union.

I’m very glad that education policy is being looked at in this context. It would be interesting to see more concrete plans and a timeframe for making this reality.

The report on the matter is here on the Newstalk site.