Troublesome Terps did a podcast on remote interpreting about a month ago which I finally found time to listen to yesterday. I won’t go into it in too much detail but a couple of things struck me during the conversation which I wanted to tease out as someone who is a trained interpreter, who likes the actual activity of interpreting simultaneously, and who has a bit of experience working in IT, in fact, quite a bit more than working as an interpreter.

When I listened to the piece, it wasn’t so much the discussion on value add that Jonathan Downie discussed – this ties in with a view I’ve expressed elsewhere about how the money in the language industry is not actually in the language bit of the industry per se, but the fact that the discussion caused me to think of two companies in particular putting effort into the self driving sector, namely Tesla and Uber, both, potentially with a view to having a fleet of self driving cars carrying out the work currently done mainly by cabbies. In the meantime, Tesla are selling you cars and learning from your driving habits and Uber are learning from your public transportation needs.

We haven’t really solved machine translation adequately yet. But it has reached a stage to where it is considered “enough” by people who are generally ill qualified to assess whether in fact it is considered “enough” for their market. Output from Google Translate is considered more than enough by lots of people every day who run newspaper articles through it to get a gist. At least one, if not two, crowdfunding campaigns are pushing simultaneous interpreting systems, often pushing its AI and machine learning credibility to sound attractive. In my view, the end game with remote interpreting is less likely to be industrial parks full of interpreting booths or home interpreting systems, and more automated interpreting. Remote interpreting allows the expectation of quality to shift.

We would laugh if any human translator translated Ghent to Cork and yet, I have seen Google Translate do this. We would also not pay the human translator for such egregious errors. But Google is free, so meh. We tolerate it and we use it much more than we ever used human translators.

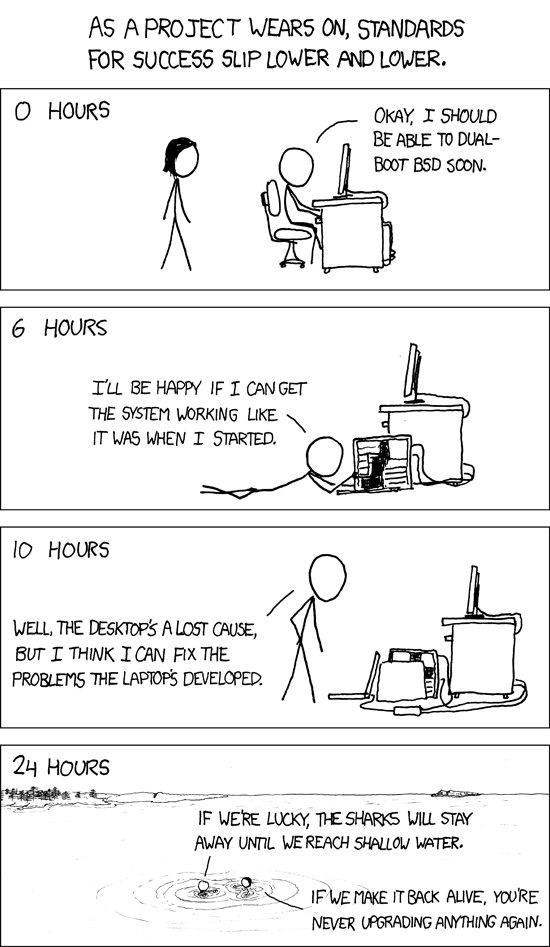

At some point, after the remote interpreting system, someone is going to AI their marketing speech about an interpreting system which cuts out the need for interpreters because Machine Learning System Blah. Both voice recognition and machine learning need to improve radically across all languages to get there to match humans but if we first bring about a situation where lower standards are tolerated (or cannot be identified) then selling a lesser quality product to the consumers of interpreting services becomes easier.

Much of what remote interpreting is bringing now is basically nothing to interpreters – I have a vision of three interpreters handling a conference somewhere in Frankfurt from their kitchens in South Africa, Berlin and somewhere in Clare, and they cannot really talk to each other in terms of who will take what slots, whether someone will catch a bunch of numbers or run out and get a few bottles of water. It seems to me that a lot of what remote interpreting is about forgets that a lot of conference interpreting is not about 1 person doing some interpreting; it’s about a team of people who need contact and coordination in real time. A lot of remote interpreting is around “this market is ripe for disruption” but the disruption is not necessarily being driven by people who know much about what the service actually involves. It misses a lot of context and perhaps it needs to do that because ultimately, the endgame may not be not about remote interpreting but non-human interpreting.