I was catching up with Troublesome Terps earlier today and was interested to have a listen to their views, and the views of their guest speaker on the question of the male female split in interpreting. You can have a listen to the piece here and they have provided some reading material which I have not yet had a chance to have a look at.

In summary though, the theme of their piece is that the gender split in interpreting is not even and there is a preponderance of women and they discussed why that may be. Amongst the items being discussed were rationales along the lines of career opportunity and whether men desired a clear promotional structure.

I found it interesting to listen to the discussion, and it covered a lot of interesting things relating to voice, and the different use of language depending on whether the speaker was male or female. If you are interested in interpreting, it is certainly worth a listen, and some of it is thought provoking.

One point which was only barely touched upon came from a passing comment of Jonathan Downie on the subject of the pipeline. I don’t think he called it that, but pipeline is the accepted term in technology for the incoming cohort of people training to come into the sector, and I think it’s a suitable term also for upcoming potential interpreters. The pipeline is core to discussions about the lack of women in the tech sector. In truth, the tech sector has a chronic lack of women, and its problem is largely two fold: comparatively few women study fields that would line them into technical roles in the technology sector, and of those who do, a lot of them drop out of the sector, or the technical roles, over time. The pipeline is often targeted as a useful and simple solution of the “if we only got more women studying comp sci, it would all be more diverse later”. For various reasons, this is probably not enough but I will come to that later.

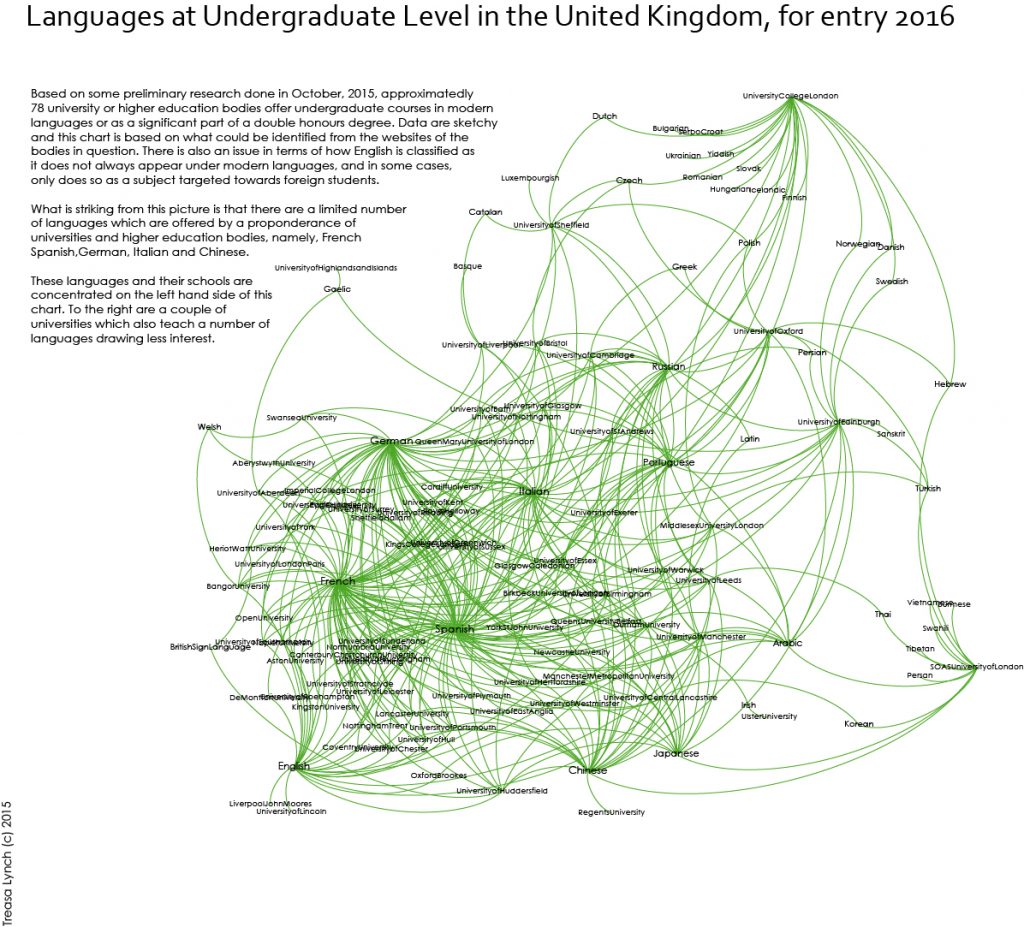

Jonathan made the comment that in the interpreting pipeline, it wasn’t so much the lack of men which he noticed at masters level as the lack of British students in the field. As it happens, I’ve previously done some number crunching in the language pipeline for the UK excluding Scotland, and Ireland, going back to 2015. You’ll find a very quick overview of the findings here. The reason Scotland isn’t included is that at the time I ran those numbers (ages ago now), I did not have access to the corresponding figures for the Scottish Highers. The key line that I want to take away from this however is this:

on average, twice as many girls study languages at school leaving stage in both the Irish leaving certificate system and at A-level stage in England/Wales

If I recall correctly, the general finger in the area calculation for the split of interpreters between female and male was around 2:1 or 3:1. It can vary slightly depending on the language.

By the way, in absolute terms, more students study higher level French in Ireland than take A-Level French in England/Wales (I can’t remember if Northern Ireland was included in those figures). Additionally, the supply of language teaching at third level is drying up in the UK with a couple of very common languages (I did research on that too) scattered across the UK and, I think, 2 or 3 schools dealing with the wider range of less common languages.

However, that is all by way of an aside. In the UK and Ireland, at least there is a serious pipeline issue with language skills for boys. In general there are at least 2 girls for every one boy studying language at advanced secondary level. However, it is wrong to extrapolate from the experience in the UK and Ireland to any other country for a variety of reasons, the key one being that other countries make a better fist of teaching their young people foreign languages in general terms (cf Finland, the Netherlands and how to make me feel inadequate Luxembourg), so the lack of a cohort prepared for specialist language courses is potentially not such an issue there. However, it looks in practical terms as though men are not following them. The question is why. I am pretty sure that the answer to that question is not straightforward, but similar to the situation for women in computer science, for example, it has its roots far earlier in the school system. There is research around to suggest that girls are caused to be disinterested in maths and science related subjects based on how they are treated as early as primary school. Socialisation may have a lot to do with how people perceive their strengths for different subjects at an early age. This is a useful piece dealing with that, although it’s six years old and I’m pretty sure there’s been more in depth stuff, particularly in terms of mathematics, in the interim.

So this is one issue with the pipeline. The second issue with the pipeline relates to the perception of the job itself, and this is where I’m going to pop up with a certain amount of speculation. Because of how the system in Ireland works in terms of winning places at university, there is evidence to suggest that a key motivator for some students in terms of their choice of university studies is the likelihood of economic success. In Ireland, that tends to be law and veterinary sciences, with pharm a little way back, and then, things vary according to economic fashion. The bottom fell out of architecture and construction related courses, comparatively speaking, a few years ago, for example. Language related careers are rarely up there with their name in lights. No one mentioned interpreting to me at school (I hardly knew they existed) and we did family research before we even tracked down translation because the school was more interested in marketing courses which were trendy when I was a young one.

So, generalising wildly, there’s a pipeline issue because boys are funneled towards technical courses and in general terms, the career of interpreter is not necessarily high profile as a good earning opportunity.

I suppose the question which next arises is what happens to men once they are in the pipeline and in the industry. I cannot really answer this question as I don’t currently work as an interpreter. I took an interest in this piece because I trained as an interpreter but work primarily in the tech sector where matters are largely inverse, and where there is a great deal of discussion on the question of women in the pipeline, women in the industry, diversity in the industry. Yesterday or the day before, Susan Fowler, a site reliability engineer, published this on her blog. My personal experience has involved men telling me the only reason women go to college is to get married and anyway they don’t know how to work (imagine a 21 year old bachelor student saying this to a female masters student with more than 10 years experience working in the tech sector and you’ll get an idea of just how stupidly obnoxious some people can be).

Is the interpreting sector sexist? I don’t know if it is, or whether the split is a symptom of wider attitudes in society which have their roots at a far earlier stage of education. It seems to me, however, that there is not necessarily a similar level of pushing men out of interpreting as can be seem in certain parts of the tech sector. Would we better off with a better balance? I think yes we probably would but that’s because in general, society is better off with a better balance across most jobs. Do I think interpreting as a skill is adequately valued? The straight answer to that is right now, and depending on your culture, probably not. Clearly, the large international organisations could not function without interpreters. Nor could the US or British armies in Iraq and Afghanistan. However – anecdote alert – when I did CPD in Heriot-Watt in Edinburgh last year – one course participant noted that historically, in her country, at certain times, interpreters tended to be men because it was a distinguished role and could not be left to mere women. Strangely enough, software development and programming, in the early days, was left to women because it was not considered to be particularly difficult (hah) and the men did more praiseworthy and important work with hardware engineering. It seems culture and perception have an awful lot to answer for on both fronts.

WordPress tells me this is nearly 1,500 words, so for the tl;dr version: it strikes me as though the lack of men in interpreting is programmed into the system quite early, and subsequently, the lack of economic value linked with the role may serve to lessen the attraction for men who tend to target economically important jobs (or perceived better paying roles anyway), or who potentially tend to get paid more when the majority of their cohort are also male.

From that point of view – and it kills me to say it – one of the best things female workers in areas which are predominantly female staffed (so nursing, teaching, interpreting, translation) could do to improve their earning potential is to increase significantly the number of men in their sector.

And a corollary of this, by the way, strikes me as being a likely motivation for getting more women into computer science and related fields – namely reducing the cost of those roles.

Okay. I might revisit this later when I am awake.